Title (as given to the record by the creator): You Can’t Say That!

Date(s) of creation: June 2005

Creator / author / publisher: Charlotte Cooper, Size Queen

Physical description: Two white pages with black text. The first page has a big red circle with a slash (a ban sign) and the second page has a photo of the author.

Reference #: SizeQueen-50-51-Cooper

Links: [ PDF ]

Ed note, 5/7/22: Charlotte Cooper apologizes for her use of the word “tranny” in this article from 2005. She didn’t know any better.

You Can’t Say That!

Charlotte Cooper

This is an old story, but it’s one that I’ve never really told in full until now. This was partly because I was afraid of the repercussions if I went public, but it was also to do with the fact that I was so outraged by the way I was treated that it was impossible for me to set down the story coherently without screaming FUCK YOU FUCKING BITCHES! At my computer screen as I typed.

The background goes like this: In 1994 I finished doing my MA in which I wrote about the nascent fat rights movement. I was also doing odd bits of volunteer work around fat, trying to get a group off the ground, and I had a minor profile for myself as someone who could talk publicly about this stuff. A British feminist publisher approached me and asked if I’d like to submit a proposal because they were interested in producing a book about fat politics. I did, and they gave me the contract in 1996.

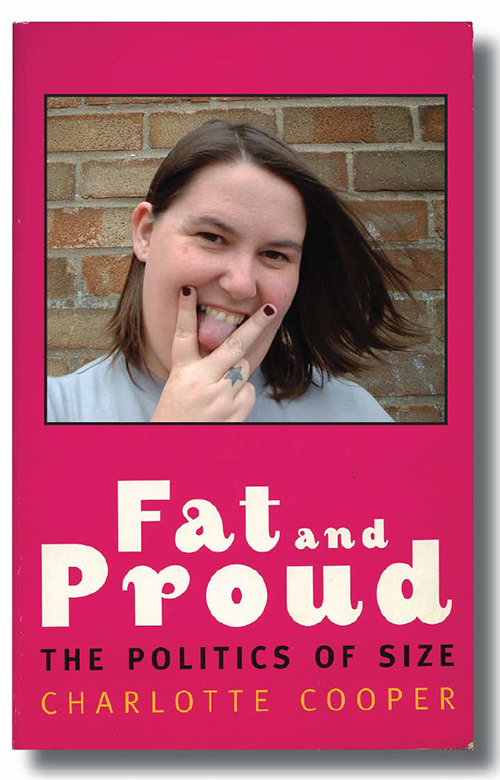

I spent a year writing ‘Fat and Proud’ and then it took another year to edit and to finally appear in shops and libraries. The reason that it took so long to get out was because the publisher and I were fighting with each other. The reason we were fighting is because, gentle reader, my publishers censored me.

I’m not talking about the editing that happens when you submit a piece of work for publication. I have no strong feelings about that, indeed. I’m only too happy to get feedback which makes the language and arguments tighter. I also understand that in this day and age you sometimes have to be diplomatic in the way that you express things because people are litigious, and that publishers and editors have their own business interests which they will want to protect. You have to shut your trap and keep people sweet sometimes. But censorship is something different. What I’m talking about is the use of threats to remove language and ideas with which the publisher does not agree because of their ideological beliefs. Two editors and the then two publishing directors threatened me with non-publication unless I removed specific words and passages.

I know this is probably obvious but I’m going to say it anyway. I think censorship is a bad idea because:

– It creates a stagnant culture of disinformation whose only purpose is to support an out of date and brittle ideology.

– Everyone should be able to make up their own minds, we should be able to access all the information possible in order to do so, and it is patronising to deliberately hide material to control a dangerous opinion or protect a population.

– You can’t remove ideas; you censor one reference which affects another, which has to be rewritten and so on, like a stack of dominoes falling.

– Social change for the better entails challenging set beliefs, not supporting them.

– Censors never look good, history always exposes them as the backwards-thinking, power-hungry, coward-slash-hypocrites they are.

Why should you care about censorship? If you’re interested in making the world a better place – whether that’s because you’re a fat dyke, or a queer of another stripe, or a member of a minority group, or just someone who wants to be understood – you’re going to have to develop new ways of thinking and being. Some people are afraid of that kind of change, they don’t want to grow and challenge their own prejudices and they can be quite nasty about it. Sometimes it’s the people you least expected who are the most obstructive. Bear this in mind, eh?

I guess you want to know what my publisher found impossible to print. Must have been pretty racy. Hmm, well, not really.

They wanted me to use the word ‘lesbian’ instead of ‘queer’ because “some women find the notion of queer unhelpful.” My publisher subscribed to the argument that queer is anti-lesbian because it is a gay male construct that glorifies anti-feminist sex. Even though I have a non-straightforward sexuality and identify primarily as a queer they insisted I call myself ‘bisexual’ in my own book. Bisexuals are fine fine people, but for many complicated and personal reasons I don’t happen to think of myself as bi right now. Queer is it for me, or dyke, and frequently, I’d prefer no label at all. Anyway, this ruling meant that other women who call themselves queer were blanketly relabelled as lesbians, which is kind of rude, when you think about it.

I had to remove a whole passage questioning the traditional feminist argument that fat is intrinsically feminine because it mentioned butch dykes and transgendered people (my publisher produced an infamous tranny-hating book some years previously and I guess they never bothered to reassess their views on the subject or listen to trans people’s criticisms of that particular title).

They changed the wording of one of my arguments without telling me because it made a vague criticism of radical lesbian feminists, and now the sentence reads as though I am supporting those women.

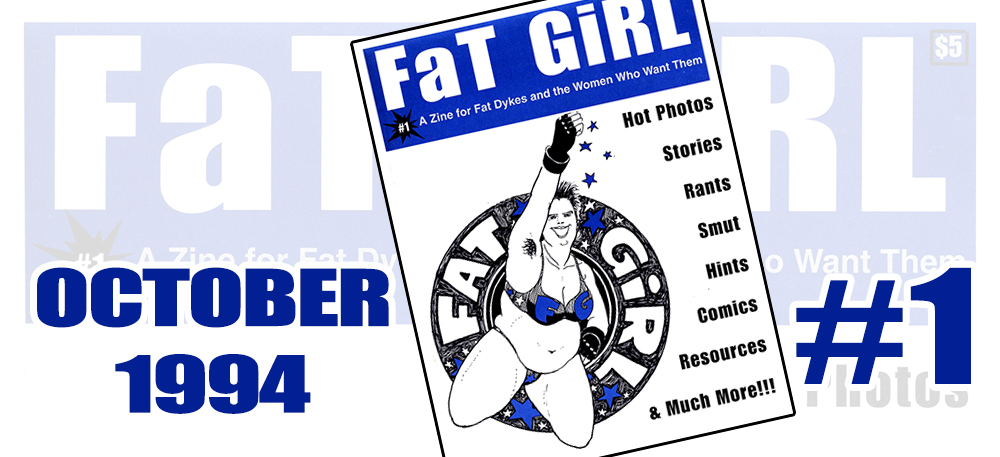

They removed all positive references ro pornography, and all positive references to non-vanilla sex. Not that the book was dripping with this stuff in the first place but there were a few mentions because I was talking about bodies and culture and, you know, this stuff comes up in that context. Anyway, this restriction actually meant removing all references to FaT GiRL, an incredible zine and major influence on me, because whilst they had never seen it they believed that it “promotes pornography,” which, of course, is evil. Smut produced by small collectives of feminist dykes for similar women and in the context of boundary-pushing articles about fat politics was so reprehensible in the eyes of my publisher that they even refused to allow me to thank FaT GiRL in my acknowledgments list or within the quotes given by one of the interviewees in my book, a founding member of the FaT GiRL collective.

They removed substantial discussions of fat women and sexuality, which included references to SM and sexphobia amongst feminists. For example, a whole brilliant argument from Fish’s excellent leatherdyke zine ‘Brat Attack’ went by the wayside. My publisher wrote to ask me if any of my other references included material which promoted pornography or SM. I said no. What did they expect me to say? “Oh yes, please destroy my work some more.”

They removed suggestions that some fat women might be complicit with their own oppression. Women have to be victims, according to the argument. This meant a whole passage about power relations between fat women and Fat Admirers was cut, against my wishes.

Each of these things seems almost petty by itself, but taken together it is quite astonishing how deliberate omission can substantially alter the tone of a piece of writing.

When I politely questioned why they would want to ditch all this exciting material without giving me a good reason why, my editor responded:

We’re a feminist press, you can’t say this stuff because it’s anti-feminist and no, we’re not going to discuss this because we know we are right.

(Oh, okay)

Your proposal said nothing about porn or SM, so under the terms of your contract we don’t have to publish anything that mentions it.

(Actually my proposal was pretty vaguely worded because debates around fat were developing like crazy at that time and I wanted to be able to future-proof myself by making a bit of space to record the as yet unknown.)

We also publish Andrea Dworkin, she’s a bit of a cash cow for us and she’ll be pissed off and go somewhere else if she sees one of our books saying that porn or SM isn’t so bad after all. (But I was allowed to criticise Kim Chernin, and her popular book ‘Womansize’ quite harshly. Chernin was also published by my publisher.)

If you don’t like this, we can sell your manuscript to this other publisher we have lined up for you. (But they’re an academic publisher, they have lousy resources, my book would be remaindered almost immediately. No thanks.)

In typical good cop /bad cop fashion my publishers allowed me one small concession.

The editors allowed me to retain a couple of ‘fucks’ and two ‘motherfuckers’ used in quotes by women that I had interviewed, and whose rawness and integrity I wanted to preserve. It seems ludicrous now but they wanted me to substitute the word ‘bloody’ which, for those of you not familiar with English dialects, has a much milder and substantially middle class ring to it.

At this stage I could have tried to sell my book to another publisher who did not make these demands. I decided to stay and fight because this particular business had a good record of promoting and selling books about body issues. They also threatened me with non-publication about four months before the book was due to be published. At the end of three years of solitary slog, I felt burnt out and unable to do the rewrites that other publishers would probably need. I was frightened of taking the step forward into litigation. I felt bullied, powerless and alone. I felt that it was better to get the stupid book out, and out of my life, and to draw attention to the censorship issues afterwards. I continue to feel ashamed about these decisions, like a sell-out, I was naive and afraid of losing my book altogether. Some people have criticised me, but they didn’t live through it like I did. I still don’t know if I did the right thing.

Excuse me whilst I yell FUCK YOU FUCKING BITCHES! At my computer screen.

It was horrible working under these conditions. I was really angry. I couldn’t believe that a publisher whose work I had previously respected could turn on an author with such ferociousness. There was no room for discussion or negotiation, just one angry letter after another. They wanted me to produce a radical new work about women’s relationship to fat, but they were not prepared to challenge their own outdated beliefs or support new debates. They were a deeply conservative radical feminist business, they did not want to help create a dynamic new discourse about women and fat, stifling it was obviously more lucrative since they constantly told me they knew what their readers wanted – but hell, I was one of their readers too! Their demands seemed like a ludicrous kneejerk reaction, I kept expecting them to admit that it was all a joke. Their censorship was so half-arsed, I offered to show them FaT GiRL but they refused to look at the source material so they had no idea what they were really censoring, and a lot of references slipped by their beady eyes. Bizarrely enough although the content was cut from the body of the book, the bibliography remains intact, with all the “pro-SM” and “pro-porn” sources intact – prizes for spotting them, my darlings.

So, the book came out, sold some copies and then quietly went to sleep. For a while I produced accompanying notes for people who wanted to read an uncensored version of events. I wrote and apologised to people who had been censored, I stopped publicising it, stopped calling myself a feminist, and cut down my involvement with fat stuff. Late in 1998 my publisher celebrated their 20th anniversary with a party at which everyone got drunk on free champagne, and the founder and one of the directors talked pompously about their policy of creating a forum for women’s voices, breaking down women’s silences. I nearly choked on my own bile – my voice obviously didn’t count.

Five years later my book sits on a shelf at home but I feel estranged from it, like it doesn’t really belong to me. I’m happy for people to read it, and I love talking to people who have felt excited by it. I think the book is important and radical, I think it’s essential reading for anyone interested in fat politics, but my heart has left it. How would I do it differently now? I’d be less naive. I’d write a tighter proposal. I’d never sell a book to a publisher that has rigid ideological values. I’d ask a lot more questions before I started work.

As for my publisher, they’re struggling along. Recently they approached a friend of mine to write a book about “the new feminism” for them but she turned them down and told them it was because she didn’t like the way they had treated me. Ha ha! In the meantime they published a feminist diet book. Oh dear.

There’s a funny coda to all of this. In 2002 I published my second book, a dirty novel. I was still contractually bound to my ‘Fat and Proud’ publisher, they had the right to refuse my subsequent book. I sent them a letter asking them if they were interested in publishing a piece of queer dyke porn that features lots of brutal SM sex and hot tranny scenes. They said no and I was free, although part of me secretly wished that they’d taken it on, I think it would have been good for them.

In an ironic twist, ‘Cherry,’ the novel in question, got seized by Canada Customs and was declared obscene. It was going to be banned because it had a fisting scene in it, which, according to Canada Customs law, is anti-woman. This is a whole other story, I’ve written about it on my website if you’re interested, but suffice to say: one day I’d really like to write a book that doesn’t get censored.

[image description: A portrait of Charlotte Cooper, a white fat woman holding her fingers in a V around her outstretched tongue. The portrait is superimposed on the cover of the censored book, “Fat & Proud,” which is the subject of this article.]

Size Queen Pages

- Size Queen Cover

- Fat Fairy Godmother

- Size Queen’s Full of it

- Why Size Queen?

- Something for Everyone!

- Take Me for a Ride, Christine lanieri reviews Venus of Chalk, the latest novel by Susan Stinson

- Fat Attitudes

- The Face of a Fat Girl: My Path into Sex Work

- I Am Not An Activist

- Shoot Me!

- This is What Fifty Looks Like

- Torocoyori

- Movement

- Fat Farm: Memories of Six East

- If a bear’s in the woods, and no one else is, does he make a sound?

- Prima Donna

- Dainty Does Ballet

- Post-Surgery = Post-Community?

- Pariah, the bleeding edge fat fashion column

- To Cut is to Heal

- It Takes a Real Butch to Admit What She Really Wants

- Jukie & Papi D

- Peach Meat

- You Can’t Say That!

- Contributor Bios

- Size Queen Collector Cards