Title (as given to the record by the creator): To Cut is to Heal

Date(s) of creation: 2005

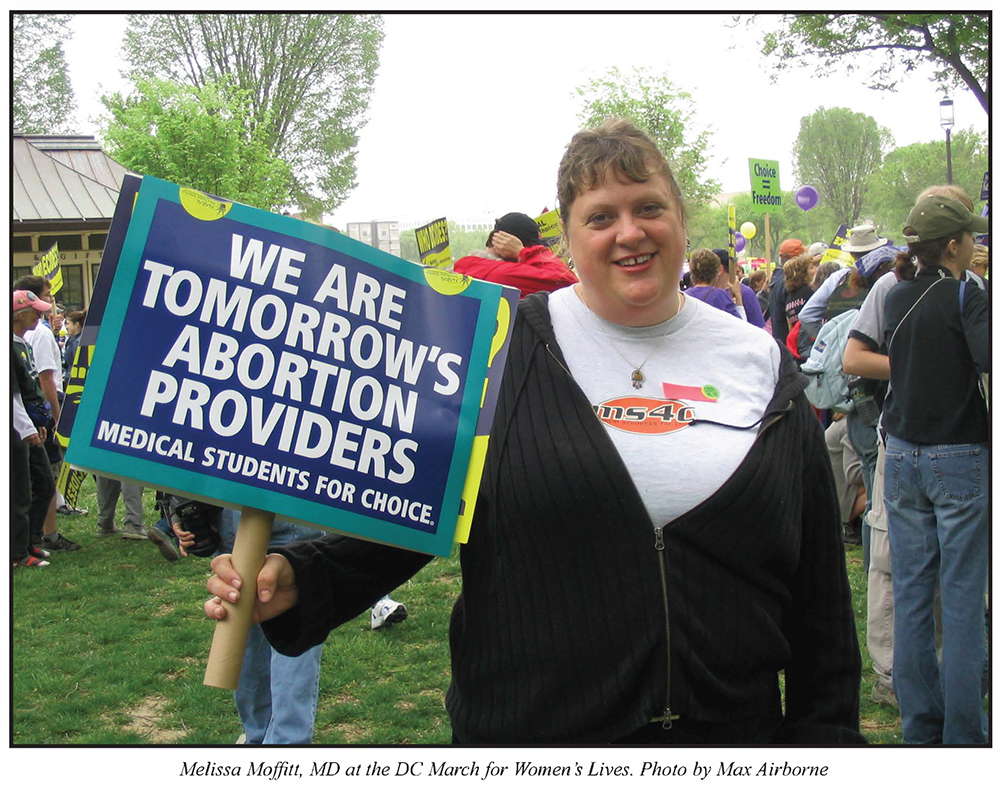

Creator / author / publisher: Elena T, Size Queen

Physical description: 2 full color zine pages with text and a photo

Reference #: SizeQueen-36-37-ToCut

Links: [ PDF ]

To Cut is to Heal

By Elena T

I decided to go to medical school because I was a science nerd and heard the call for abortion providers. During my junior year of college, I worked in a hellhole of an abortion clinic. It was somehow well respected by the academic and pro-choice communities. Everyone there (except for the beaten patient advocates) was a complete asshole. I decided I needed to become a doctor to save everyone else from doctors and somehow martyr myself for the good of humanity or some shit like that. (This is the kind of crap you have to deal with as an adult if you grow up in a suburb.) I hoped that the people who chose medicine were assholes, not that medicine made them assholes. So here I am now a third year medical student, doing clerkships in the hospital. This is the first time I am actually responsible for some kind of patient care; as little as it is – mostly writing notes in the patient’s charts and having the doctors sign them because it is libel for me to sign them as my own work. I am doing the surgery clerkship first. I wanted to get it over with. It really sucks. I have to be at the hospital by 5 am, wake up all my patients, do a physical exam, write in their chart, morning round at 6:30, surgery at 7:30, go to class, then afternoon rounds, and go home to collapse to a frozen dinner and 5 hours of sleep. This is how the brainwashing begins.

So I work with surgeons. They do surgery on everything they can fix, like, oh … “morbid obesity.” What a nice term – you are fat, therefore you die. Unless, of course, the surgeons fix you. Thus, the gastric bypass. This is the surgery where the stomach is basically cut off leaving a pouch the size of a small bouncy-ball – smaller than a mouthful. It leaves all the nerves intact so the stomach still feels full (early satiety.) It also keeps the person from ever eating a meal again in their life. It also helps that all the swallows they are able to take for the first two months are liquids only. (The liquid, of course, is being provided by pharmaceutical companies – since the person is going to need all their nutrients for the day in four swallows of food. This was only previously possible on the Jetson’s.)

Most of the patients at the hospital where I work are poor women of color. It is the county hospital in a large Midwestern city. All the surgeons are older, rich, white men, trained by the army. Learned their trade in Korea! Nam! Now they have comeback to save the “US of A” from fat people! Excuse me, morbid obesity. The surgeon’s motto “Heel with Steel” fits in so many ways.

When I first heard that my surgery team was doing a gastric bypass I almost threw up. I was disgusted. The other two students wanted to go and I told them I never wanted to see one. Then more gastric bypasses were done and my turn came up.

The surgery started out with lots of fat jokes and racist remarks like “big mama.” The closeted dyke resident said the big antibiotic pill Ms. W_ had to take were too big for her stomach , so she would have to sit on the pill and crush it under her big ass and mix it with applesauce. The complaints started with her urinary catheter – the smell of her crotch. The only thing I could think of was how much better it would smell after she had lost 100 pounds and had diarrhea all day. And then there were obligatory remarks about getting smashed by her when we rolled her onto the table.

The gastric bypass is performed by stapling across the stomach (usually leaving it hanging there) leaving a small pouch into which the esophagus drains. Then part of the small intestines is cut and reattached to the stomach pouch. The rest of the stomach, which is just hanging out in the abdomen, is still connected to the first part of the small intestines into which the bile I duct and pancreas drain. The end of that tract is reconnected into the small intestines where the food is draining.

The mortality rate for the procedure is 1%. Complications include wound infections, leak of stomach secretions, strictures at the new holes made, lung edema, and emotional disorders. Long term – outlet obstruction, depression, malnutrition, and dumping syndrome. Dumping syndrome is something that occurs after eating characterized by sweating, dizziness, weakness, flushing, headache and pain. This is a quote from the basic text, the essentials of surgery.

“Bariatric surgery produces effective weight control … Follow up in 502 of 519 patients revealed the maximal mean weight loss is achieved in two years with small increase over the ensuing nine years, reflecting those patients who had staple line breakdowns and a few other pouches with high calorie liquids or repeated snacks …. [but] the rate of rehabilitation of jobs or further schooling is high.”

Ms. W_ got her surgery. When she finally gets out of the critical care unit, she is all smiles. She asks, “When can I eat?” and then just laughs and laughs. She sits on the old extra large bed and takes occasional puffs from the smoking ventilator tube. Then Ms. W_ got a wound infection. Her wound is about two feet long, six inches deep, and gapes four to five inches wide. Oozing puss. We rinse it out and the water drips down into her crotch. None of the others want to dry her off. They think she is disgusting. A few days later we deem her ready to leave the hospital, with her infected wound. We arranged for a home nurse to come to her house and wash and pack the wound. Ms. W_ has said she can not do it herself. We seem to have converted her into hating her body as much as we do. We tell the doctor who performed the surgery about the home nurse. He says: “No. She doesn’t need a nurse to come to her house. Let me tell you something. The reason why they get this way is because they are lazy and manipulative. They need to take care of their own bodies now.” He looks at me directly, “It is called tough love.” I look down to keep from screaming and realize that I am adjusting my blood-stained blue polyester scrubs made for men to cover up my own luscious belly. I am living a nightmare. We go into Ms. W_’s room. Somehow, she did not hear the discussion, though it happened right outside her door. The doctor informs her that it is time for her to take care of herself. Dress her own wound – the one we inflicted on her. She starts crying. She has the ghetto drawl of a poor, black, Midwestern woman. There is no one home to help her except her two little girls. “I can’t even look at this thing,” glancing at her abdomen, “How am I supposed to do this?” The doctor replies, “No. It is time for you to do this yourself.” “O.K., doctor,” Ms. W_ says, “You know best.”

Everyone’s thoughts are confirmed. She is manipulative and lazy. Though love is the best approach to these people, they really come around. There is absolutely no thought to why Ms. W_ hates herself so much (let alone why we hate her so much.) She is on her way to being cured and becoming a better person.

There are two other people in intensive care now who have had gastric bypasses. They have both had complications. One is dying. She is 46 years old and has had many horrible encounters with medicine. She has permanent disabilities from some of the inert medications she was given years ago for diarrhea. She had bacterial sepsis twice. She also weighs 350 pounds. Gastric bypass is one of the few surgeries she has [sic] not had. She is now doped up on morphine, versed, ativan and whatever else to sedate her and keep her from feeling intense pain. She holds a stuffed animal when she can remember to ask or the nurses decide to give it to her. Her hands are tied to the bed because she can’t remember where she is and pulls at her many drains and tubes. No one comes to visit her.

I said out loud in front of another medical student, “I really don’t want her to die.” My colleague replied, “I know, I don’t really want her to die either, but bariatric surgery makes such an impact on their lives, and morbid obesity has a mortality rate of four to five percent a year. The literature really supports it.” All I could respond with was, “I did not think she was going to die this year.” The brainwashing has begun.

Size Queen Pages

- Size Queen Cover

- Fat Fairy Godmother

- Size Queen’s Full of it

- Why Size Queen?

- Something for Everyone!

- Take Me for a Ride, Christine lanieri reviews Venus of Chalk, the latest novel by Susan Stinson

- Fat Attitudes

- The Face of a Fat Girl: My Path into Sex Work

- I Am Not An Activist

- Shoot Me!

- This is What Fifty Looks Like

- Torocoyori

- Movement

- Fat Farm: Memories of Six East

- If a bear’s in the woods, and no one else is, does he make a sound?

- Prima Donna

- Dainty Does Ballet

- Post-Surgery = Post-Community?

- Pariah, the bleeding edge fat fashion column

- To Cut is to Heal

- It Takes a Real Butch to Admit What She Really Wants

- Jukie & Papi D

- Peach Meat

- You Can’t Say That!

- Contributor Bios

- Size Queen Collector Cards